He had been one of the greatest basketball players ever to call Dayton home.

Steve Johnson – Bill’s neighbor growing up on Dennison Avenue in West Dayton and a lifelong friend who admits “I might be a little prejudiced” – believes he was “better than Dwight Anderson,” the hoops sensation most consider to be this city’s top basketball product.

While Johnson’s assessment showed favoritism, it wasn’t that far-fetched.

“You hear about Dwight Anderson, Frankie Sanders, the Paxson brothers and some others, even my own brother, Cornelius Cash,” Lorenzo said. “But Bill was just a phenomenal ball player.”

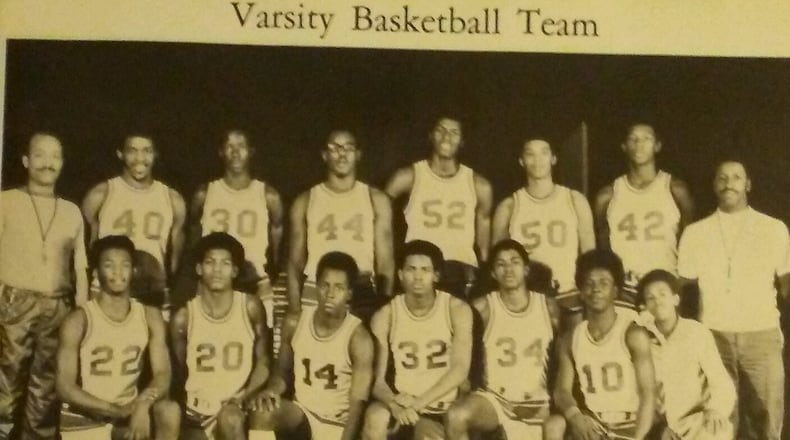

He was the high-scoring, 6-foot-2 guard on the 1970-71 Dunbar team that carries the double-edge distinction of being the best team from the Miami Valley not to have won a state championship.

Though the Wolverines' five starters would all get college scholarships (four to D-I schools) and three would be drafted by the NBA, they ended up getting upset by Columbus Walnut Ridge in the Class AAA title game.

Bill went on to Ashland College where he was a two-time All-American and scored 1,746 points in just three seasons.

He was chosen by the New Orleans Jazz in the seventh round of the 1975 NBA draft, but signed with the Virginia Squires of the rival American Basketball Association. He later played pro ball in Belgium and the CBA before joining the Army and becoming a standout on the All-Army team that won two military world championships.

After his career ended and he returned to Dayton, he again was compared to Dwight Anderson, whose career ended up decimated by drug and alcohol abuse.

“Bill’s life became an almost carbon copy of Dwight’s,” said Norris Cole, who grew up with Bill, went to Dunbar with him and remained his friend.

But there was one difference. Dwight got help from basketball friends with connections and, after decades in decline, he reclaimed his life in recent years before dying in September.

Bill continued to live outside the limelight and the stroke robbed him of his communication skills.

“That last time I visited I wasn’t able to understand a lot he was saying and it was really disappointing,” Lorenzo said.

"Finally he went to one of the drawers in his room and pulled out two framed pictures of himself when he was with the Squires. One was an action shot and one was him standing there in his warmup.

“Man, that was something to behold. I looked at those photos and he looked at me and after a while we both were laughing. He really brightened up.” Bill the Thrill was back.

“That’s my last memory,” Lorenzo said quietly.

Last Saturday, Nov. 7, Bill died at age 67.

He leaves behind three children – William II and daughters Autumn and Jasmine – as well as his sisters Deborah and Nicole, his brothers Todd and Damon, other relatives and lots of basketball friends, who, like Cole, stressed: “He is a legend from our community and should not be forgotten.”

Dr. Richard “Ricky” Gates – now the superintendent of Jefferson Township schools, but once the point guard on that 1971 Dunbar team – said:

“If Bill’s a forgotten player, it’s just by people who never played against him. If you had, you’d never forget him.”

‘Basketball became his outlet’

One of the only people to get the better of Bill the Thrill on a basketball court was Ruby Johnson, Steve’s mom.

When he was in middle school, Bill had moved in across the street from the Johnson’s house at 921 Dennison. That’s when he first discovered his love for basketball.

“We had a hoop on our garage and Bill was there shooting all the time,” Steve said. “Well, one Sunday when we got back from church, he was there and my mother told him he couldn’t be playing at our place on Sunday mornings when we were in church.”

But on the following Sundays, as the Johnson family prayed and sang at the Church of Christ, Bill’s idea of heaven was that driveway hoop and he kept coming back.

“Finally, my mom had enough and she got him told real good,” Steve laughed. “She ran him off and said, ‘No more playing out here, Bill!’”

A few days later, with the help of Steve and anther neighborhood kid, Robert “Boney” Nelson, Bill fashioned his own court in a vacant lot next to his house and just behind the Pantorium Cleaners.

“We dug a hole and put a pole in and then nailed plywood to it for the backboard,” Steve said. “And we just ran the ground down 'til it was hard enough that we could dribble there.”

As Boney remembered it: “That basketball court was like something from a movie. We turned the light around on the laundromat so it lit up the rim and we could play at night.” “And Bill was the master of the court,” Steve said. “He shoveled snow out there to play in the winter. In the summer he might be out there 'til 2 or 3 a.m.”

“Our father didn’t play sports so Bill didn’t pick up a basketball until eighth grade and he wasn’t very good at first,” said Todd Higgins, who’s almost 13 years younger than Bill and, like Damon and Nicole, has a different mother than Bill.

That outdoor court became everything to Bill. Along with a place to hone his hoops skills, it became a refuge for a fractured home life that lacked a solid foundation after the divorce.

“Basketball became his outlet,” Todd said. “It was his sanctuary, his canvas.” And his artistry really started to develop once he got to Dunbar.

“What really made him successful was Coach (Ben) Waterman,” said Cornelius Cash, the Wolverine’s 6-foot-8 star who later amassed 1,245 points and 1,068 rebound in three seasons at Bowling Green (back then college freshmen weren’t eligible for varsity) and was a second-round pick of the Milwaukee Bucks in 1975.

“It started with Coach Waterman. He was like Mick training Rocky Balboa in the movies. He was no nonsense. He was old school.”

The Dunbar starters – the Cash brothers, Skip Howard, Gates and Bill Higgins, who was also known as Wild Bill – all had separate, but meshing roles on the team.

“Bill was a tremendous scorer and we needed offensive firepower, he could just take over a game,” said Gates.

The team, coached by George Galloway after Waterman became an Ohio State assistant, went 24-2 and beat Hamilton Taft – led by future Kentucky All American and NBA standout Kevin Grevey – in the regional finals and then out-battled a tough Cleveland East Tech team in the state semifinals.

Kids in the area idolized the Wolverines.

“I was 11 or 12 then and lived around Dunbar and watched them practice,” said Hank Benton, now the girls' basketball coach at Trotwood-Madison High School. “I remember listening to that championship game against Walnut Ridge on the radio and being really hurt when they lost.”

The Dunbar starters all shined in college: Cornelius Cash and 6-foot-9 Skip Howard went to Bowling Green and won All-MAC honors and 6-foot-6 Lorenzo Cash ended up the leading scored on the Colorado State team. Gates was a three-year starter at Kent State and won All-MAC honors on the court and in the classroom.

At Ashland, Bill averaged 18 points a game as a freshman, 28 as a sophomore and 30 as a junior.

“On the court he could do whatever he wanted to do against anybody he wanted to do it to,” said Ashland teammate Bruce Curtis, who was from Roosevelt High School.

As an All American, Bill was invited to Walt Frazier’s camp at Upsala College in East Orange, N.J. said Boney Nelson: "Back then the invitees could bring one person along and he brought me.

"Well, all these potential pros were playing, so he and I hooped it up against a bunch of other cats. It was really something.

“And after that, Dr. J invited him to his camp.”

Once in the ABA, Higgins really did become Wild Bill, say some who knew him.

“He came home with fancy coats and a new car and all he wanted to do was share it all with everybody,” said Cole. “He had a free heart.”

And yet, said Johnson, "He didn’t have the foundation to be able handle all that. When you’re a pro, there are a lot of doors opened to you, but some of them you just don’t want to go through.

“But Bill did.”

Memories of Bill

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the funeral service will be kept a family affair for now, Todd said.

That means that Bill’s buddies are left to memorialize him with stories shared amongst themselves.

“Me and Bill played a lot of 1-on-1 basketball over the years,” Lorenzo Cash said. "And the honest truth is that he’s the only person I could not beat.

"I remember playing to 10 once out there on that court next to his house. I had him down 9 to 1 and I kept telling myself, ‘OK, don’t miss this last shot and you got him!’

"But I missed and, Buddy, even though I never played defense so hard in my life, he kept scoring and beat me.

“We lived over on Bolander (Ave.), it’s Stewart Street now, and I remember walking home through DeSoto Bass with my ball tucked up under my arm and my head down. I might even have shed a tear or two.”

Bill’s two younger brothers both were awed by him.

“We were a lot younger, but once we got in the first and second grade at Louise Troy (Elementary), we started to fall in love with basketball, too,” Todd said. "It got to the point where we both wanted to wear his high school number 22.

"And something pretty amazing happened when I got to Dunbar in 1980. The freshmen were still using those same jerseys the varsity wore in the 1971 state finals. They were passed down all those years.

“We didn’t want them because they were old, but then, there it was -- number 22 – and I was able to wear the exact same jersey my brother wore.”

Once at Ashland, Bill wore No. 15. But while his jersey number went down, his ability to score went up.

“In college I had an assistant coach who graduated from Ashland,” Gates said. "On day after practice, he asked if I wanted to go watch the game with him. I said, ‘What game?’ And he said, ‘Ashland to see Bill the Thrill!’

“Bill threw in 55 that night.”

Over at Bowling Green, Norris Cole went to school with Skip Howard and Cornelius Cash.

“After one game we were over a Cornelius’ apartment and who rolls in late after he had played in Ashland, but Bill,” said Cole.

"We’d been talking about how well Cornelius did – he was the big story in Bowling Green – and Bill’s just sitting there, happy go lucky like always. Finally, we asked him how he did.

"On good nights we called him Bill the Thrill and on regular days he was just Wild Bill. So we’re like, ‘Whaddya have? 25? 30?’

"He just sat there smiling and said, ‘Naaah, you can just read about it in tomorrow morning’s paper.’

“And, sure enough, when we read the story the next day, it told how Bill Higgins was the top scorer in the nation!”

Sometimes you don’t need a picture.

A boxscore can tell the story of Bill the Thrill.

About the Author